Just about to book my flight tickets for around Thanksgiving, while simultaneously taking down serious notes for the “won’t, might and will kill to buy” list with mom, my dad casually asks me, “Are you there to work or rather blow off everything in the crazy thanksgiving frenzy?” I was just about to market our dear Modiji’s “FDI” scheme when the website showed the INR conversion of the flight fare. After making a few mental calculations, I concluded there was either an error in the INR-$ rates on the website, or my math tutor owed me a full refund and a written apology.

Much to my surprise, it was neither. The Indian rupee touched its lowest ever on Thursday, crossing 69 to a dollar mark, pummeled by high crude oil prices, geo-political concerns and looming fears of a global trade war. What does it mean for individuals, companies, exporters, home loan borrowers and the economy in general? Here’s a primer:

How does the currency market operate?

Like any other commodity, demand and supply determine a currency’s price or the exchange rate. A stronger demand for the currency will strengthen the exchange rate or push up its price and vice versa.

If a currency is depreciating it implies that its value has fallen in relation to another currency. In the present context, the value of rupee has fallen or depreciated from about Rs 66 to a dollar to about Rs 69 in less than two months.

Why does the exchange rate fluctuate every day?

Banks, corporations, brokers, individuals and governments buy and sell currencies every day. That explains the daily fluctuations in the currency prices according to changing demand and supply situation.

Why is the rupee falling?

There are two primary reasons on the rupee’s current slide.

Crude oil prices: After a brief lull, crude oil prices have started climbing rapidly, cantering close to USD 75 a barrel on geo political concerns. The US is building pressure on its allies to stop buying oil from Iran by November, sending oil prices to move up sharply.

The spike in oil prices has pulled down the rupee, by pushing up dollar demand. Oil marketing companies will have to pay more for every barrel of crude. This has raised the demand for dollars, contributing to the rupee’s fall.

Trade war fears: Concerns over an escalating global trade war triggered by the US and China’s retaliatory tariffs on goods imported from each other has had bearing on currencies across the world.

In March, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order imposing tariffs on foreign made steel and aluminum. It has been justified on grounds of fighting back against an “assault on our country” by foreign competitors. China has imposed retaliatory tariffs on several US products as a response.

The Chinese yuan has fallen sharply in the last few sessions, amid looming fears of a global trade war and growing protectionism. This triggered a dollar flight from many emerging economies including as US based funds pull out money from bonds and equities in these markets and park it closer home to weather the uncertainty. The spurt in dollar outflow has pulled down most Asian currencies, including the rupee, which hit a record low on Thursday.

What’s in it for the economy?

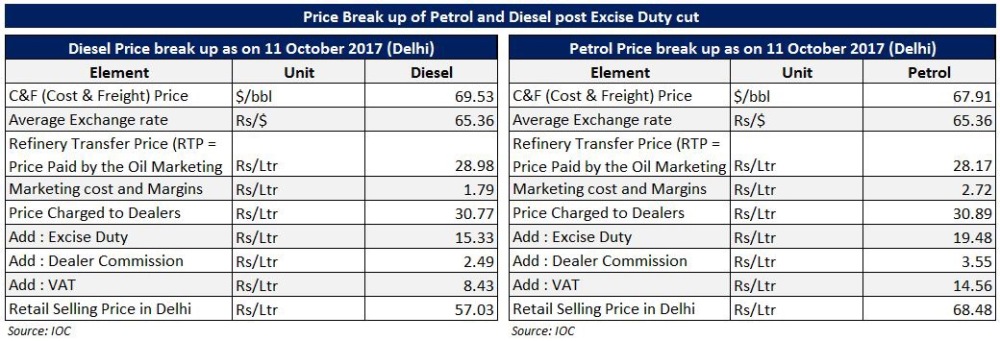

A depreciating rupee will make imported goods costlier. So, expect computers, imported mobile phones and gold to become costlier. It will also make crude oil imports costlier, prompt oil companies to hike petrol and diesel prices. Costlier transport fuel will knock up prices of most goods and stoke inflation. A weak domestic currency affects the current account deficit (CAD) — the gap between foreign exchange inflows and outflows.

What about inflation and interest rates?

A weak rupee will fan inflation, by making imported goods costlier. Petrol and diesel prices will go up, which will knock up prices as cost of ferrying goods go up.

Elevated inflation will also mean that the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) may look at raising lending rates to contain the price line. Besides, the RBI may also be prompted to keep interest rates high to maintain India’s attractiveness as a debt market and woo dollar inflows. So, home loan EMIs may be creeping up soon.

Should I be worried?

You better be, if you have plans to study and travel abroad. A weaker rupee implies you end up paying more to buy dollars to pay for your fees. If earlier you were planning to pay Rs 13.2 lakh ( at 66 to a dollar) for a USD20,000 course in an overseas university, now the cost will go up to Rs 13.8 lakh (at 69 to a dollar) even though the fee in dollar terms remains unchanged. So, your study loans might go up.

What about foreign travel?

If you were planning to go for an overseas vacation, you better set aside more money. A weaker rupee implies you end up paying more to buy dollars to pay for your, air tickets, hotel tariffs, shopping and other expenses. A hotel room that cost Rs 13,200 ( USD 200) a night ( at 66 to a dollar ) will now cost you Rs 13,800 ( at 69 to a dollar), even though the tariffs in dollar terms remains unchanged, forcing you to buy more foreign exchange before you head out for the vacation.

What about exporters?

If you are exporter, a weaker rupee would mean your earnings in rupee terms will go up.

How will it affect companies?

The slide in rupee will hurt profitability of many companies. Companies that borrowed dollars from overseas banks will be the worst hit as repaying loans will become costlier. Imported raw material such a copper, aluminum and machinery will turn costly and squeeze profit margins. This may prompt companies to raise prices of consumer goods such as cars and televisions.

What are the policy options to stem the rupee’s fall?

As the country’s central bank Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has a responsibility to prevent economy from currency shocks. Central banks world over intervene through buying or selling of currencies through banks. To prop up a weak rupee, the RBI sells dollars in the market. The government can also ease foreign investment norms to encourage dollar inflow.

What are the other options to arrest the rupee’s slide?

Moral suasion

• Sometimes central banks convince banks to carry out certain acts through non- official persuasion as opposed to official instructions or a statutory decree.

•

• RBI can persuade banks and FIs to raise cheaper dollar denominated funds from overseas markets and then lend these to domestic borrowers in the form of rupee loans.

•

Quasi sovereign bonds

• The government may decide to float quasi-sovereign bonds to attract longer-term NRI funds

• The Resurgent India Bond (RIB) 1998, and the India Millennium Deposit (IMD) 2000 were also similar bonds targetted at channelising NRI savings into India

• The government may also ask some public sector companies to raise funds abroad.

Export boost, import curbs

• The RBI can decide to make import payments in a staggered to prevent a persistent drain on forex reserves.

• Higher customs duty on luxury goods and other consumer items will dampen demand and slow down dollar outflow.

Why is there a lurking worry over India’s current account deficit (CAD)?

An economy, similar to an organisation, has earnings and spending. The balance of payments (BoP) is a statement of account foreign exchange earned and spent.

The BoP statement is classified under two broad heads—the current account and capital account. Funds through routes such as the foreign direct investment (FDI) are shown the capital account as these stream in over a period of time.

There are also spending and earnings that are “current” in nature. These include export earnings, import payments, foreign exchange flows from intangible services exports (such as tourism), and NRI remittances or money transferred by non-residents to relatives back home among others. These are clubbed under the current account.

What does a deficit or a surplus in the current account signify?

A current account deficit (CAD) means that there is more outflow of capital from the economy than inflow, which is not desirable. A surplus would mean that the economy is selling more to the rest of the world than what it is buying

What does the latest data on CAD show?

India’s CAD has inched to 2 percent of GDP. Analysts fear that the dollar outflow, if it persists at the current rate, could push up CAD to close to 3 percent of GDP. A widening CAD can necessitate dipping into the pool of foreign exchange reserves. So far India has been able to finance its CAD without drawing on the USD430 billion foreign exchange reserves.

Source/ Statistical Reference : The Economic Times, Money Control.